Copper’s Place in Pennsylvania German Metalwork

Copper played a significant role in the lives of 18th century Pennsylvania German (also known as Pennsylvania Dutch) households that far exceeded its better known place hanging over a fire in the form of a tea kettle. Copper vessels filled with hot coals served as warming pans to take the chill off of bed linens. Large copper apple butter kettles, as well as copper stills used for making alcohol, were fixtures on many farms.Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, also had its place in the form of candlesticks and lamps that could be hung or placed on a table, cow bells for herders to keep track of their livestock, as well as furniture hardware such as escutcheons, pulls, and knobs.

Pennsylvania German early crafts and craftsmen have been sought after by collectors and received recognition through study due to the well-crafted and colorful nature of such objects as sgrafitto pottery, painted furniture, Fraktur manuscripts, carved wooden butter molds and tin cookie cutters, among others.

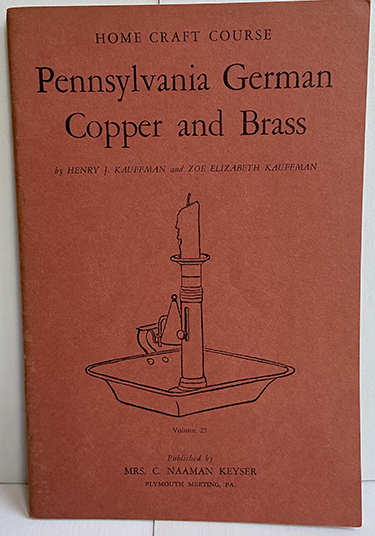

Pennsylvania German Copper and Brass, published in 1947.

Pennsylvania German Copper and Brass, published in 1947.Photographs courtesy of Historic Trappe.

Henry J. Kauffman and Zoe Elizabeth Kauffman, authors of Pennsylvania German Copper and Brass, volume 25 in the Home Craft Course series, pointed to a primary reason that items made of copper and brass haven’t received the same recognition.

“The most important single reason is that few of the products were marked by their makers and that it is, therefore, unusually difficult to ascertain if they were made in America or were imported from Europe or the Middle East,” the Kauffman’s state in their book that was published in 1947.

They further go on to explain that this failure to be able to identify the work is what has ”prevented the romance” of collecting it on the same scale as silver and pewter.

An illustration of a copper vessel that served as a fluid container

An illustration of a copper vessel that served as a fluid container to fill early lamps, featured in PA German Copper and Brass,

Home Craft Course series, Volume 25, 1947.

“In only a few isolated cases have pieces, now highly treasured, been marked and owned by descendents of coppersmiths, but these are the exceptions rather than the rule,” the Kauffmans explained.

The Kauffmans pointed out that items such as tea kettles bearing the “touch marks of their makers” on the handles were more likely to be found than markings on stew pans, fish kettles, and coffee or chocolate pots.

More recently, Lisa Minardi, an author, historian and the Executive Director of Historic Trappe, home to the new Center for Pennsylvania German Studies and two historic house museums from the Muhlenberg family of Pennsylvania, discussed the scarcity of scholarly examination of some areas of Pennsylvania German decorative arts in the book Pennsylvania Germans: An Interpretive Encyclopedia (JHU Press, 2017).

In the book, which pays tribute to the historical and cultural legacy of the Pennsylvania Germans, Minardi, a contributing author, discussed a broader reason there has been a lack of attention to certain objects in the realm of Pennsylvania German decorative arts.

“Although there exists a substantial historiography on the general subject, the study of various object types is far from representative,” Minardi says.

Minardi notes that subjects such as Fraktur, furniture and architecture have received ample attention unlike other subjects that have received little to no focus of study.

on the tophandle of a copper hot water kettle, from the collection of Historic Trappe.

“Most studies tend to focus on the more distinctive and ornate examples that are not representative of what typical Pennsylvania German families owned,” she says.

Minardi’s contribution to the Interpretive Encyclopedia includes various metals and their link to Pennsylvania Germans in the household, including serving as the medium used to make objects such as lighting devices, cooking vessels, stoves for heating, as well as tools and implements.

“Most copper and brass products made in Pennsylvania were made from reused or imported raw materials, as native copper was not refined in adequate quantity until the nineteenth century,” Minardi says. “Among the most common copper objects were hot water kettles or teakettles, noted for their distinctive gooseneck spouts and dovetailed or soldered tab bottoms, which were frequently marked on the handle by the maker,” Mindardi says..

Historians in search of identifying names and data about early copper and brass craftsmen have benefited through the discovery of advertisements found in such publications as the Lancaster Journal. In their book, the Kauffmans included an ad placed in the Journal by coppersmith Samuel Hubley on January, 16, 1802 when he “respectfully aquaints (sic) his friends and the public” as to where he will be conducting his work on North Queen Street in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

The ad listed the types of wares Hubley made that included stills, tea kettles, coffeepots and saucepans, before stating the following:

Historic Trappe.

“The above articles will be sold on the most reasonable terms, but which, (and the goodness of the work), he hopes to merit and receive the encouragement of a generous public.”

The advertisement concludes by making a plea for old pewter, copper and brass, which, according to the Kauffmans, indicates Hubley’s difficulty in obtaining raw material with which to work.

“Gussets in the sides of copper kettles, patches on warming pans, and skimmers worn thin indicate the scarcity of the metals and the frequent attempts to salvage what would be quickly discarded today,” said the Kauffmans.

Earlier, in an ad placed in the Pennsylvania Herald and York Advertiser on August 22, 1792, coppersmith William Bailey of York Borough was seeking out the immediate help of journeymen coppersmiths:

“Who are complete workmen at stills, to whom 18 dollars, per month will be given by the Subscriber, and provided with meat, drink, washing, and lodging,” the advertisement states. “None need apply but sober industrious persons. Their money shall be paid at the end of the month.”

Of the over forty coppersmiths at work in Pennsylvania in the 18th century, Minardi notes that many were German including Jacob Eichholtz, Frederick Hubley and Frederick Steinman of Lancaster, as well as Matthias Babb of Reading and William Heiss of Philadelphia.

According to Minardi, there is a vastness of scholarly examination that awaits particular objects despite pioneering scholars publishing studies since the early twentieth century.

“Pennsylvania German arts have captivated a broad audience for more than a century and generated an extensive historiography for future scholars to build upon,” she says.

Visitors to Historic Trappe can see a wide variety of 18th century copper as well as iron, brass, and pewter artifacts on exhibit when the museums re-open in 2021.

Resources:

Also in this Issue:

- Copper Artist Ronald Stauffer Honored by Amazon

- Robin Tost: Giving Form to the Discarded

- Copper Sculptor Ruth Asawa Celebrated by USPS With Line of Commemorative Stamps

- Copper’s Place in Pennsylvania German Metalwork

- Grounds for Sculpture Remains Open for Winter Viewers